Watching Question Time this week (special scheduling with Jeremy Corbyn and Owen Smith) I was struck, not for the first time by:

- What a charming, principled, honest man Jeremy Corbyn appears to be.

- The certainty that the British public will elect him prime minister when hell freezes over.

The last thing we want in our elected representatives is honesty. For all that we rail against the disingenuousness of MPs, we want comforting lies, not inconvenient truths – usually, a version of “all will be well, spending on public services will increase massively, the economy won’t suffer and no one’s taxes will rise.”

So it is with crime fiction, mysteries and thrillers. We don’t want the truth, or at least not until the very last chapter. We want to be teased with it, fed a few lies along the way, have the facts dangled tantalisingly out of reach.

Hence our on-going obsession with the unreliable narrator.

At the CrimeTime festival on the island of Gotland last month, there came the inevitable question about the reliability of narrators in crime writing. I drew a breath, ready to launch into a well-rehearsed explanation of why I love and use the device of the unreliable narrator so much. But no. Malin Persson Giolito had an entirely different take on the subject. She wanted to know whether there is such a thing, in fiction, as the reliable narrator.

What a good question. And one that could apply equally well to real life. Whenever we relate events, it seems to me, we bring a vanload of baggage that inevitably colours our interpretation and therefore our narration. Our mood, our relationship with our audience, their on-going reactions, how we felt about the event, how we felt about the behaviour of ourselves and others will all impact upon how we tell the story. Someone else, with exactly the same experience, might describe events quite differently. Which is correct? Both, of course, because neither of us is lying per se. On the other hand, neither of us is telling the entire truth. We are telling our own version of it. We are narrators, but not entirely reliable.

The police are well used to the unreliability of witnesses. People remember different things, place emphasis differently. They even invent and embellish memories. Conflicting witness accounts are a difficulty the police grapple with on a regular basis. They learn never to take a complaint entirely on face value.

I’m not about to suggest, because I wouldn’t dare, that victims of crime are rarely entirely blameless themselves. What I will say is that victims invariably feel a sense of guilt, a belief that on some level they contributed to their own misfortune. Victim blaming, arguably, begins with the victim himself: the car-theft victim who left his keys in the ignition, the man who was beaten up after swearing at some kids on the street. When describing the event to the police, these people have an entirely normal tendency to minimise their own role in what transpired. To lessen their own perceived guilt, people tell less than the whole story. The job of the detective is to fill in the gaps.

Even stepping away from criminality for a second, we all have secrets, things we’ll never tell another living soul. (If you don’t you probably need to get a life!)

We’ve all done things we’re ashamed of, have views that we might not feel comfortable airing in all situations. We none of us tell the whole story.

And so it goes in fiction. Story telling is a constant balancing act, between the knowledge the author has and must hold back until the time is right, and the desire of the reader to know as much as possible. And so it should be, because there is nothing like a question in the reader’s mind to get the pages turning, and turning, and turning.

My ten favourite unreliable narrators:

- Amy and Nick Dunne in Gillian Flynne’s Gone Girl

- Pi in Yann Martel’s The Life of Pi

- Huckleberry Finn in Mark Twain’s novel of the same name.

- Teddy in Denis Lehane’s Shutter Island

- “The black pawn” in Joanne Harris’s Gentlemen and Players.

- Tessa in Lisa Gardner’s Love You More

- Julia in Tess Gerritsen’s Playing With Fire.

- Mrs De Winter in Daphne Du Maurier’s

- Jenna in Clare Mackintosh’s I Let You Go

- And Lacey Flint in Now You See Me (of course!)

To be amongst the first to see all future posts, as well as being automatically included in all sneak previews and give-aways, sign up for my newsletter on the Book Symposium page.

I get asked (more or less every day now) whether and when there will be a new Lacey Flint book. Some readers (the ones I prefer) beg me to write another Lacey story, telling me how much they’re missing her and Joesbury. Others demand another story in the manner of a hard-to-please restaurant customer, as though I can rustle up a book as easily as a well-stocked chef can produce a rare steak.

It’s becoming the question I most dread (followed closely by why did you change your name from SJ to Sharon?) because the honest truth is that I just don’t know. I will be very surprised if I never return to Lacey and her friends, but for the moment, I have other stories to tell.

I think that’s the key. My books all begin the same way. I have an idea that intrigues me, sooner or later other ideas will slip in alongside it and a story will start to form in my head. At that point, and not before, I ask myself who should help me tell this tale. If it’s set in London, on or around the river, if it involves a good chunk of hard detective work, and maybe the maverick thought process of a couple of off-the-wall coppers, then the chances are it’s a Lacey book. But if it isn’t, then no amount of forcing on my part will make a square peg fit the round hole.

I appreciate this might be frustrating and even annoying for ardent Lacey fans but whilst there may be some authors who can write to order, I’m simply not one of them. I believe that writers must write for themselves, first and foremost. To do otherwise is to risk producing a book that satisfies no one. I have to write the story that is in my head and in my heart. This year, it has been that of a woman, hiding away from the world, who, quite by chance, sees something that forces her back into it. Last year, Daisy in Chains, arose from my interest in twisted love affairs and before that, Little Black Lies was the tale of a friendship torn apart by an act of neglect with tragic consequences. None of these stories were right for Lacey. Maybe the next one that comes to me will be. When that happens, I’ll unlock my chest of flint and silver, pull out the puppets and give them a dust off. Until then, my stories will have to be told by others.

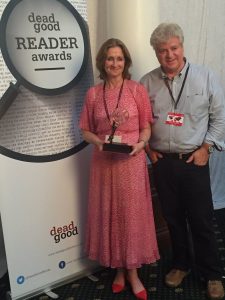

Little Black Lies has won the Dead Good Linwood Barclay award for the most surprising twist. Voted by readers and in their second year, these popular awards were presented at the Theakston’s Old Peculier Crime Writing Festival in Harrogate in July, at a ceremony presided by Mark Lawson. Other winners included Stuart Macbride, Robert Galbraith and Peter James.

Please help me find my blue haired muse.

Maggie Rose is the enigmatic, reclusive protagonist in my latest book, Daisy In Chains. She is a criminal barrister and true-life crime writer and such is her success in getting cast-iron murder convictions overturned that the police dread the very sound of her name. She lives alone, never giving interviews or allowing her photograph to be taken. Few have met her, few even know what she looks like, which is odd because Maggie is rather wonderfully, eccentrically gorgeous.

I honestly cannot remember how and where I came across this photograph. I can only assume magic was at play, because as soon as I saw this strikingly beautiful blue-haired woman, I felt an instant connection. I knew who she was, her name and everything about her. I knew the story she had to tell.

I kept the picture on my computer ‘desktop’ screen, all the time I was writing Daisy In Chains. She has been my constant friend for two years now.

I dislike novels that rely too much on overt description of personal appearance. Show me a scene in which a character looks in a mirror and muses over his/her own hair/eyes/jawline and I’ll show you a book consigned to the bin. I try to avoid ever telling my readers outright what my characters look like, but I have this theory that if I can see them in front of me all the time I’m writing, then a subtle amount of description will creep into my text and the characters will take shape, even become vivid, for the reader too.

Two years now the woman with the blue hair has played a huge role in my life and now, when Daisy is about to be unleashed on the world, her muse is still a mystery.

I’d love to find this woman, even if her hair is no longer blue. I imagine she’s a model, possibly an actress, but I have no real idea. If anyone recognizes her, please let me know.

Spooky fun fact: I did not spot the Daisy brooch on her coat until a few days ago.

There’s been a right royal rumpus these last few weeks about a bit of tidying up. Clean For the Queen, in case you missed it, is a UK wide plan to spruce up our towns and villages in readiness for the Queen’s 90th birthday. An idea that has proven hugely unpopular on social media.

My mate and I, out dog walking, were talking about it as we passed through a field in which travellers camped three years ago. I offer no opinion on travellers, but the piles of rubbish they left behind have been a real eyesore and a danger to wildlife since. We’ll do it, we agreed. We’ll rope in a few mates.

Meanwhile, to hear the “Wow-Just-Wow” brigade you’d have thought the nation was being marched in leg-irons to Buck House to scrub the royal lavatories, pick up corgi poo and leave our first-borns behind to be palace chimney sweeps.

Allan Crow in Fife Today accused the scheme of trying to turn the clock back to the 1920s, of ‘tapping into a notion of royal deference that is antiquated in 2016.’ He wasn’t alone. Articles talked about people feeling patronized, about the scheme being elitist and out of touch, doomed to fail at the outset. There were even accusations of racism. Tee shirts with the slogan “Spic and span, Ma’am,” caused a problem, apparently. No, I can’t see it either.

And so it went on. ‘We should pick up our litter as we go,’ people cried. ‘This is why we pay our taxes.’ ‘It’s the council’s job, not mine.’ ‘If it weren’t for Government cut backs, there’d be no need to drag hard-working families from their hard-earned leisure time.’ ‘And what has the Queen ever done for me?’

Meanwhile, thousands of people all over the country did what they always do when a problem needs solving. They got on with it. Clean for the Queen is actually turning into a massive success because the people of the UK, for the most part, are entirely sensible. They know that Keep Britain Tidy has been organizing annual litter picks for years and that this Clean For the Queen business is nothing more than a catchy slogan.

We live in a filthy country. I say this from one of the posher bits. Thirty million tonnes of litter are dropped every year according to Keep Britain Tidy, making the UK one of the worst offenders in the world.

It’s our problem. It’s not the Queen’s, because this was never really about the Queen. It’s not the Government’s or our local council’s, it’s not the travellers’ because they are long gone. It’s ours, because we have to live in the mess. I had to walk past that cess-pit every day. Well, no longer. I’ve cleaned it up.

Ma’am, you are welcome..

Out in my new car last weekend, I witnessed a fascinating little drama unfolding in my rear view mirror. There were road works on the main ring road around Oxford. Two lanes had to merge into one and the predictable happened. The vast majority of fair-minded, law-abiding, decent folk pulled over to the right hand lane and began queuing. The few, with an innate sense of entitlement, who seem genuinely to believe that their time is more valuable than ours, and that the rules of fair play do not apply to them, began speeding down the left. In doing so, they greatly slowed down the progress of the queue. We in the right fumed silently, swore under our breath, but otherwise did nothing.

And then, on the horizon, appeared the silver-clad knight on his white charger, in the form of a modest Black Renault hatchback. He (I’ll bet my last tenner it was a bloke, women just don’t do this sort of thing) pulled out into the left lane and stayed where he was. Nothing could get past him. The queue of traffic continued towards the lights, order and fairness had been restored. We breathed a collective sigh of relief.

Only for a few minutes. Rage began to build in the wings-clipped cars of the left hand lane. Horns started to sound. Lights to flash. Fists were shaken. Surely the Black Renault would crumble and pull over? No, he stood firm. A counter attack was staged. A large silver Mercedes mounted the kerb, swung its way past Black Renault and thundered on ahead, yelling abuse from his open driver’s window. A second and a third car followed suit. Black Renault pulled closer to the left kerb and further insurrection proved impossible.

By this time I was agog with admiration. I desperately wanted to pull out into his lane and travel at his speed, just to show solidarity but didn’t quite dare. Well, I was in a new car and I didn’t want it scratched. I’m also a bit a wimp about confrontation. I was praying for someone else – a bloke, in a bigger car, to do it, but no one did. Black Renault made his stand alone.

This all went on for quite some time. It took probably twenty minutes from the queue forming to my getting through the lights and pulling away. I was desperate to see whether Black Renault would hold out.

It became a compelling little parable for everything that’s wrong in the world. Most people do the decent thing. The selfish few ignore the rest and gratify themselves. One lone ranger stands up for what’s right. He’s attacked, he’s vilified. He’s made to suffer for his courage. The rest of us admire, wish him well, but do nothing.

I got to musing (to the extent it was possible, I could hardly take my eyes off the mirror) about whether what I was seeing in the action of the impatient car drivers, honking, swearing, furious at being thwarted, was actually the true nature of evil. I spend a lot of time, unsurprising given my job, thinking about what evil really is, and I’m increasingly coming to the conclusion that it isn’t to be found in the sadistic, psychotic serial killer or the deranged mass murderer. For one thing, there are very few of those around anyway and for another, most you can name will be very damaged individuals themselves.

I don’t think it’s to be found in the crime of passion, a momentary loss of control in the face of great provocation is hardly evidence of evil.

I think evil is much smaller. I think the con artist, who systematically and relentlessly preys upon elderly folk, tricking them out of their much needed savings, is evil. I think the ruling men in Muslim countries, who force their country’s women into leading shadowy, servile lives, are evil. I think those who hide behind the anonymity of social media to kick with impunity at those who are suffering, are evil.

Evil, I think, is a combination of a personal sense of entitlement and a disregard for the rights of others. It isn’t big and grand and impressive. It’s small and selfish, rather pathetic really, except in the impact it has upon others. And, except in the possibility of its escalation.

Black Renault stood his ground. He held the left lane. They did not pass. He is an unsung hero of our age, as far as I’m concerned. I salute him.

A few weeks ago Sacrifice, the movie version of my first book, went into post-production. The process has been long and, at times, somewhat torturous. To those about to embark on the same journey, here’s what I learned:

1. Choose your producer well. Give the option to someone who is as passionate about the story as you are. All else being equal, they’ll make the better film.

2. Be realistic. I was warned that fewer than 5% of optioned books ever become finished movies. The chances are against you. Enjoy the kudos of having an optioned book, enjoy the “money for nothing” that is the option fee and, to the extent that you can, never think of it.

3. Have patience. Films can be years in the making. Months will go by with nothing happening (that you know of) followed by a frantic flurry of activity. You’ll get close, something will go wrong, you’ll start over again. Jenga-like, the tower grows as the pieces slot into place: finance, director, screenwriter, lead talent, sales agents. Later, insurance companies, studios, directors of photography slot in too, but if just one piece falls out, even a piece of a piece (one of several financial backers) the whole tower can collapse. Stay calm. That Jenga tower may be rising again from the rubble. Or the bricks may be scattered across the carpet. Either way, there’s nothing you can do. Chill.

4. Think outside the box that is your book. A movie is not an audio book with pictures. Nor should it be judged on how slavishly it sticks to the chapter and paragraph of the book. A book may take many hours to read, its film version, rarely more than two hours long, will see much material cut or condensed. It must be so. Similarly, aspects of a book that succeed in written form may not translate. In Sacrifice, Tora spends long pages staring at a computer – this couldn’t possibly work on screen – the writer had to find a new way.

5. Get the balance right. Most contracts will allow for you, the author, to be consulted over the script. Make the most of this. You know this story better than anyone. You are in a stronger position to spot the problems, the missed opportunities. Read and comment upon every version you’re sent, but bear in mind that the story isn’t yours any more. Someone else’s passion and creativity will take it forward now and, if you’re lucky, make it better than the original. And be nice. Remember how hurt and annoyed you get when someone criticizes your book? Well, screenwriters are the same. Getting the script right is a continual wrestling match between author and screenwriter. Eventually, the screenwriter should win.

6. Stay onside. Hopefully you’ll love the emerging movie but, if you don’t, keep it to yourself. You are part of the production team and they have the right to expect 100% loyalty on your part. Never, ever, criticize the movie version of your book.

7. Don’t tell the world. When it looks as though everything is going ahead, the temptation to make The BIG ANNOUNCEMENT is almost overwhelming. Don’t. Remember the words of my US publisher. “It’s not a movie until they’re buying the popcorn.”

8. Dare to dream. 5% of optioned books do become films. Some are huge box office successes, most much more modest, but however successful they become, the process of seeing something that started inside your head, being brought to life by creative and talented people, is – quite simply – extraordinary. And worth the pain.

Thanks to Dead Good for kind permission to use this feature.

The Hollywood adaptation of Sacrifice, starring Radha Mitchell, Rupert Graves and David Robb, has completed its final week of filming in Ireland.

Based on the 2008 debut novel by British author, Sharon Bolton, Sacrifice is the story of consultant surgeon, Tora Hamilton, who moves with her husband, Duncan, to the remote Shetland Islands, 100 miles off the north-east coast of Scotland. Deep in the peat soil around her new home, Tora discovers the body of a young woman with rune marks carved into her skin and a gaping hole where her heart once beat. Ignoring warnings to leave well alone, Tora uncovers terrifying links to a legend that might never have been confined to the pages of the story-books.

Written and directed by Peter A Dowling and featuring Ian McElhinney, Liam Carney and Joanne Crawford, the film is expected to be released in 2015 or early 2016.

Bolton, who visited the set in its penultimate week, described the experience of seeing her novel come to life as ‘thrilling.’ She said, ‘The footage I saw was eerie, disturbing, beautifully atmospheric and intensely moving. Peter Dowling and his team have captured perfectly the essence of Sacrifice, and are telling a story of raw human emotion against a background of superstition and mistrust.’

Background information:

Producers:

Cheyenne Enterprise (Los Angeles): Arnold Rifkin (the Die Hard series, The Whole Nine Yards, 16 Blocks, Hostage etc)

Subotica Films (Ireland): Tristan Orpen Lynch, Aoife O’Sullivan (Miss Julie, Young Ones, Perfect Sense etc)

Luminous Pictures (UK): Peter S Lewis

Sales Agents:

Meyers Media Group (Los Angeles): Lawrence S Meyers (Unfaithful, An American Haunting etc)

Director and Screenwriter

Peter A Dowling (Flightplan, Reasonable Doubt, Stag Night, etc)

Cast includes:

Dr Tora Hamilton: Radha Mitchell (Finding Neverland, Melinda and Melinda, Phone Booth, Man on Fire, etc)

The weekend just gone (I’m rushing to get this posted on a Friday) was quite possibly one of the best for a very long time, and yet was so subtle in its joy, so filled with quiet, gentle pleasures, that I hardly realized how good it had been until early Monday morning when I was walking Lupe across the fields and reflecting.

It all kicked off with Bonfire Night, the backdrop to so many of my best childhood memories. Decades on, just the hint of gunpowder on the wind and I’m back in that steadily climbing excitement of foraging wood, building the best fire in the neighbourhood and then guarding it against the threat of theft or sabotage by rival gangs. Bonfire night was so bad-ass back then, with its all-too-real danger of being burned alive, hideously scarred or just lured away from our parents in the dark. These were the days when teenage boys hurled lit ‘bangers’ into the crowd; and the crowd considered it an acceptable annoyance.

Now, as we join the slow, wrapped-up-warm snake of villagers winding its way up the hill, I watch my twelve year old storing up his own memories of Bonfire Night as the annual village fireworks display becomes a sort of outdoor, cold, masked ball. Everyone we know is here, but so wrapped up are they in woolly hats and mufflers, so cloaked in darkness, that we hardly know them until they’re upon us.

Later, we ate outdoors around the bonfire, with burning faces and freezing feet, asking ourselves what it is, exactly, about fire that fascinates us so. We had no answers, we probably never will, we just accept that it does.

The next day was Remembrance Sunday, a day I’ve loved since I was young, mainly because its cheesy patriotism reaches out to the drama queen in me, but also because it’s an occasion, like Guy Fawkes Night, when the community comes together for a single purpose. Later, in the glorious afternoon sunshine, six of us went running. Golden and warm, with berries hanging jewel-like in the hedgerow, it was the perfect late autumn day. I completed my first ever 10k. We ate roast pheasant and toffee apple pudding for dinner.

So there you have it, warmed by memories of my own, I caught a glimpse into those of my son. With good food, a blazing fire and warm, spiced wine, I was surrounded by people I’ve spent the last decade learning to know and care for. There was time with my family, and a new personal best.

We have a tendency, I think, to be continually looking forward, waiting for the next big event: a big holiday, Christmas, a promotion at work, exams being over, the launch of the mass market paperback (eek!) and by continually doing so, we sometimes lose sight of what’s offered to us in the here and now.

But last weekend reminded me that life can bring precious gifts when we least expect them, and that a chill, perfectly ordinary, weekend in November can be considered one of the best of times.

With tiresome regularity do we hear that crime fiction is getting too violent (most recently at this year’s Bristol Crimefest); that complex plotting and intriguing characterization have been replaced by torture porn; that sales-hungry authors are scrabbling to write the goriest, most sickening scenes of sexual violence.

Publishers collude, we’re told, festooning book-jackets with terrified (but still beautiful) semi-clad females.

They’re typically written by women, these books. Men don’t dare write anything so nasty, because, goodness, what would it say about them if they did? Actually, they’re usually written by lesbians, because we all know they hate men.

Sorry, I’m not buying it anymore. The gratuitous crime novel is a cultural myth. It’s a bogeyman. It’s akin to the snuff movie, invented to scare us, to fill column centimetres in newspapers. In real life, though, it’s as scarce as an albino Dodo with heterochromia.

Steve Mosby was the first to suggest the emperor might actually be starkers. “Where are these best-selling and influential crime novels with tortured naked women on the cover?” he tweeted. I replied: “Mine has a worried woman in a tight anorak, does that count?”

It didn’t. But it got me thinking. It got me panning the internet for pictures of naked women. (It felt a bit creepy after a while) I did find one or two scantily clad ladies (on book covers, you understand) but in such a massive genre, you’d expect one or two, surely?

So if the gratuitous cover can’t be borne out, what about the rest?

Well, I read a SHED-LOAD of crime fiction and honestly can’t remember the last time I abandoned a book because of its ‘gratuitous’ violence. This is CRIME, let us not forget, and without violence, or at least the threat of it, there can be no crime that we care enough about.

Of course, books appear from time to time, in which violence is used to grab attention, to disguise a weak storyline or poor writing, but generally speaking, these books don’t do terribly well. They are quickly forgotten. There is no evidence that I can see of a rising trend.

Let’s try and break it down further, shall we? We’re told books have ‘more gory descriptions of killings.’ Well, I’m not sure about this either. Most murders in most crime novels take place off the page. Val McDermid, in my company, once said, ‘the violence is not in my books, it is in my readers’ imaginations.’

We also hear about “autopsy scenes dragged out for several pages”? Well, this may be true but it’s entirely understandable. A couple of decades ago, we saw a surge in interest in forensic science, which gave rise to the post mortem scene, to a focus on maggots, decaying flesh, and the stories etched on the human skeleton. We saw more dead bodies on our pages, but our interest was in the science underpinning the investigation, not in the violence that had caused it in the first place. And, key phrase: a couple of decades ago. This is hardly new!

So, I don’t accept that there is a rising trend towards gratuitous crime. Or, if there is a slight upward curve, that it is at all out of proportion to what is happening in reality. Culture reflects reality, remember, and in a world where the worst atrocity can be broadcast in all its gory-glory within seconds, we should naturally expect the censorship of our fiction to relax accordingly.

And what does it matter anyway? Violence in our culture is healthy and normal. Make-believe is how we come to terms with our fears and make ourselves feel better. Nervous Nellies claim that a violent culture sparks violence in real life but they’ve yet to offer any proof and, frankly, I’ll take a lot of convincing. Check out the personal histories of some real-life, sadistic predators. How many of them were avid readers?

Now, I know nothing will change just because I’ve written this. As long as there are crime writing festivals we’ll see panels brought together to discuss “The Violent Tide Sweeping our Genre,” “Women Writing Violence,” “Bloody Lesbians in Crime.” Looking ahead to Theakston’s 2040, I see myself on a panel called “Lavender, Lace and Lethal Stab-Wounds” with a couple of other dippy old bats, discussing the increasing propensity for little old ladies to pen shockingly violent novels. We’ll all pretend to be terribly interested and a little bit worried about the future of our genre. And we’ll all know we’re talking bollocks.

The rise of the gratuitously violent crime novel is as fictitious as the genre it claims to be shaping.